In one of the biggest upgrades to the U.S.-Japan alliance since its inception, the U.S. will revamp its command in Japan, giving it a “direct leadership role” over American forces in operational planning in both peacetime and in potential crises, the countries' defense chiefs and top diplomats announced Sunday, as the allies’ look to counter what they say is an increasingly assertive China.

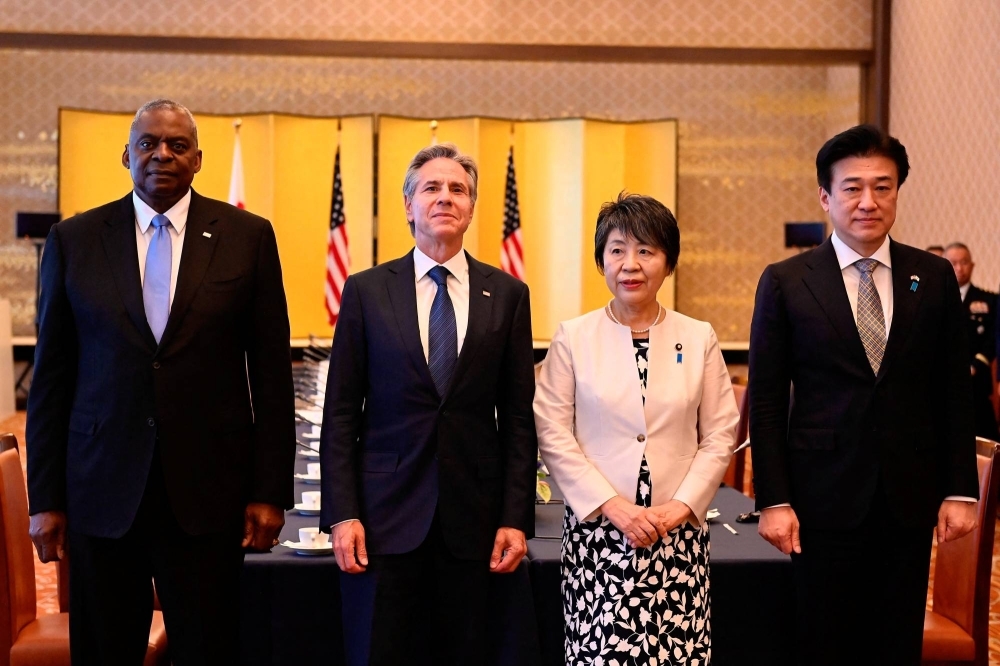

The announcement, which came after “two-plus-two” talks between Foreign Minister Yoko Kamikawa and Defense Minister Minoru Kihara and their U.S. counterparts, Secretary of State Antony Blinken and Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin, was among a number of fresh defense and security initiatives unveiled after the meeting, the first since January last year.

“The United States will upgrade the U.S. Forces Japan (USFJ) to a joint force headquarters with expanded missions and operational responsibilities,” Austin told a joint news conference after the meeting. “This will be the most significant change to U.S. Forces Japan since its creation — one of the strongest improvements in our military ties with Japan in 70 years.”

According to Austin, the unified command would be upgraded in a step-by-step manner.

“To facilitate deeper interoperability and cooperation on joint bilateral operations in peacetime and during contingencies, the United States intends to reconstitute U.S. Forces Japan as a joint force headquarters reporting to the Commander of U.S. Indo-Pacific Command,” according to a joint statement released by the officials.

Through the phased approach, the new USFJ joint force headquarters will “enhance its capabilities and operational cooperation” with the Self-Defense Forces’ own new permanent joint headquarters, which is due to be established before the end of this fiscal year, which ends next March.

The new USFJ headquarters will also “assume primary responsibility for coordinating security activities in and around Japan in accordance with the U.S.-Japan Treaty of Mutual Cooperation and Security,” according to the statement.

The move means the reconfigured command will take over operational command responsibilities of the roughly 55,000 personnel stationed in Japan, from the U.S. Indo-Pacific Command — some 6,200 kilometers away in Hawaii — amid rising fears that a delay in bilateral communications could cost the allies dearly in any potential conflict.

Plans for the U.S. command upgrade gained steam last month, following comments by Austin that basing a four-star commander in the country is something the Pentagon was “looking at very closely.” While U.S. defense officials said the commander would remain a three-star general, Austin did not rule out the possibility of having a more senior officer in the role eventually.

Tokyo is believed to have long sought a four-star commander, who would be expected to wield operational command.

Japan and the U.S. will launch working groups to hash out the details of the move.

Meanwhile, some observers have argued that the effectiveness of the new structure could partially depend on the level of funding it gets, whether for additional assets, personnel or infrastructure, from the currently Republican-controlled U.S. Congress. This issue could become highly politicized, particularly if former President Donald Trump returns to the White House and shifts Washington’s geopolitical priorities.

James Schoff, a defense expert at the Sasakawa Peace Foundation USA, said that increased regional threats — including over self-ruled Taiwan and from nuclear-armed North Korea — as well as changing defense technologies have “put Japan more on the front lines of a potential regional conflict,” necessitating “quicker joint decision-making and careful coordination of the countries’ defense capabilities.”

In the joint statement, the officials also struck a strident tone on China, which observers say has played a crucial role in the allied decisions to push these changes forward, claiming that Beijing’s “foreign policy seeks to reshape the international order for its own benefit at the expense of others.”

They reiterated “strong objections” to China’s “unlawful maritime claims, militarization of reclaimed features and threatening and provocative activities in the South China Sea” — pointing to unsafe encounters at sea and in the air, efforts to disrupt other countries’ offshore resources exploitation and the “dangerous use of Coast Guard and maritime militia vessels.”

Following the two-plus-two talks, the four officials also held their first-ever Cabinet-level talks on beefing up the effectiveness of the allies’ nuclear and conventional military deterrence and response capabilities.

Those talks focused on the U.S. commitment to providing “extended deterrence,” including nuclear weapons, to protect its ally, with the ministers reiterating the need to “reinforce” the alliance’s deterrence posture and manage “existing and emerging strategic threats through deterrence, arms control, risk reduction, and nonproliferation,” according to a separate statement.

The officials are also believed to have discussed the direction of a reported new joint document covering the issue, amid what the allies say are growing nuclear threats from countries such as China, North Korea and Russia.

Although not mentioned in the statement, the new document, reportedly set to be completed by the year’s end, will aim to bolster the alliance’s deterrence effect by articulating Washington's unwavering commitment to defending Japan and providing direction and clarity on what kinds of situations Japan might face in order for the United States to retaliate, including with nuclear weapons.

It will also give “ministerial-level permission for the two militaries to take concrete steps to enhance extended deterrence,” said Masashi Murano, a Japan chair fellow at the Hudson Institute.

Since 2010, the two sides have held working-level discussions on the issue, but hurdles have limited their breadth, particularly about how Japan might politically and militarily support a situation in which the U.S. might use nuclear weapons.

At the two-plus-two meeting, the four officials also agreed to deepen information-sharing and defense-industrial cooperation, saying the aim is to “maximally align our economic, technology, and related strategies to advance innovation, strengthen our industrial bases, promote resilient and reliable supply chains, and build the strategic emerging industries of the future.”

The allies’ recently launched Defense Industrial Cooperation, Acquisition and Sustainment (DICAS) framework will be key in this regard, with its goal being to advance missile co-production efforts, build supply chain resilience, facilitate ship and aircraft repair and strengthen research on emerging technologies.

Against this backdrop, the allies discussed efforts to establish a production system in Japan for the Advanced Medium-Range Air-to-Air Missile, the latest version of which is designed to be deployed on all variants of the F-35 stealth fighter jet. Japan has purchased nearly 150 of the advanced fifth-generation aircraft to replace its aging F-2 fighters.

They also agreed to strengthen production in Japan of Patriot Advanced Capability-3 (PAC-3) surface-to-air guided missiles in order to export them to the U.S., which has faced stockpile shortages as it provides military support to Ukraine in its efforts to repel Russia’s invasion.

With the move, Japan also hopes to build up its own domestic defense industry. The Patriot plan, however, has hit a roadblock amid media reports that a shortage of the missiles’ seekers, which guide them in the final stages of flight, could delay additional production by years.

The Hudson Institute's Murano said that in order to identify and rectify defense-related supply chain challenges, the allies must “swiftly develop and adopt a federated supply and logistics management tool and increase transparency in each other's supply chains and logistics.”

While cooperation on Patriots faces obstacles, the U.S. and Japan have moved ahead with a broad deal reached during a leaders’ summit in April to repair U.S. warships and aircraft in Japan and jointly develop and produce other advanced weapons. The historic meeting in Washington also saw Tokyo pledge to act as America's "global partner" in maintaining the rules-based international order and countering China’s growing assertiveness.

Last month, U.S. and Japanese officials held their first talks to identify areas for closer industrial cooperation following Tokyo’s revision of strict defense export guidelines in March.

Although Sunday’s announcements were meant to ensure the alliance continues to work on a common agenda, the road ahead remains littered with challenges.

For instance, the weak yen presents a “substantial challenge to the alliance, not only inhibiting Japan’s ability to procure expensive foreign-made equipment but also requiring increased financial resources to support the planned SDF enhancements,” said Misato Matsuoka, an associate professor at Teikyo University.

There are also potential political hurdles as both countries face leadership changes in the coming months. While the U.S. is set to hold a presidential election in November, Japan will see a number of elections over the coming months, including the LDP leadership poll in September, developments that could presage volatility.

“Biden’s decision not to contest the November election has turned him into a lame duck,” said Robert Ward, the Japan Chair at the International Institute for Strategic Studies, noting that this could render some of the recent agreements vulnerable to change, especially if Trump is reelected..

But even if the U.S. and its allies managed to continue bolstering their military capabilities, experts warn that too much deterrence without equal diplomatic engagement could be one of two plausible paths to conflict in Asia, with the other being a deliberate attack.

These two paths are intertwined, they warn, as efforts to lower the risk of a deliberate attack using strengthened deterrence may actually make an accidental clash more likely, particularly as diplomacy increasingly takes a back seat.

culled from Japan Times